Choristers leaving the College Chapel after early morning prayers at Eton College, Berkshire. The famous public school is offering junior music scholarships in an attempt to attract bright and musically gifted boys to the school. The blur was used in this case to anonymise the pupils. The camera was sat on the ground, propped up with a the lens hood because I didn’t have a tripod and wanted the motion blur. The lens was a Canon 16-35 f2.8L and the camera was an EOS1D.

technique

Chicken or egg? Workflow or mess…

Which came first… the Chicken or the egg, digital imaging or workflow?

One of the rather brilliant side effects of teaching is that you had to look very long and hard at your own practice to make sure that it will stand up to the examination of younger and more eager minds. I have taught workflow on and off for a few years now and I have come to the conclusion that all photographers should get theirs checked every once in a while to make sure that they haven’t fallen into the bad habits trap.

It doesn’t take much time and going through what you do and why you do it with an experienced teacher of these things is a great idea. I have also discovered how useful having a go at a proper edit of someone else’s pictures can be. Photographers are rarely their own best editors and it is a brilliant exercise to do an edit of a job where you give no attention to including pictures just because were hard to take or to pictures that you really like but don’t help tell the story. Captioning should also be part of that exercise because we all make assumptions when we do our IPTC that a disinterested party wouldn’t make. All in all, I thoroughly recommend these exercises to you.

In a rather tongue-in-cheek reference to the Alcoholics Anonymous “Twelve Step Plan” to beat addiction, I developed the photographers 12 step plan to get a good, dependable and repeatable workflow. It doesn’t matter that you can cut twelve steps down to seven or eight if you need to work fast and it really doesn’t matter that step twelve was “relax and put your feet up” anyway. What actually matters is that you have a tried and tested way of getting your valuable pictures from the camera to the client and back them up without making silly mistakes that cost you time, image quality and (worst of all) money.

For years I have been “quoting” the Hippocratic oath that Doctors and other medical folks take when they take up their calling. I have put “quoting” in inverted commas because it turns out that the phrase I have always used isn’t part of the oath at all – it’s just a line from a film!

Anyway I’ve been saying this; “First, do no harm”. It works for medicine and it certainly works for photographer workflows because the idea is that you never damage the original file – always working on a copy. Of course, with Jpegs that have had anything more than very light compression applied that means that you have already sacrificed some quality – but I don’t want to go down the whole RAW Vs Jpeg road again.

At some point in the future I will publish an updated version of the photographer’s 12 step plan with a step-by-step explanation of how my own workflow works but for now I wanted to just outline it. Remember that this can be edited down so that you have fewer steps if needs be:

- INGEST/IMPORT – get the images and any supporting files from the camera into the computer. Applications designed to ingest or import files look inside folders and sub-folders on the memory card in a way that you might not be able to do by simply copying files from the card yourself. It’s important to note that this is one of the easier steps to cut out if you are in a real hurry.

- FIRST EDIT – make an initial selection of the images that you are interested in. At this stage you can dispense with very badly exposed frames, pictures where the focus has been missed, where important people have their eyes closed or pictures that are just not very good.

- COPY – move a copy of the selected images to a new folder.

- RENAME – give the selected pictures a new name. Some clients will have a formula that they want you to follow but otherwise try using a simple word identifier, followed by a six‐digit date and then a sequence number. All good software has the ability to batch rename and sequentially number files. A set of portraits of Tony Blair shot on the 3rd of April 2011 might be blair-110403-001 through to blair-110403-204. The exact formula that you pick isn’t as important as having one that works for you. The filenames that the camera assigns are not good enough and not unique enough for professional use.

- CAPTION – using the IPTC metadata fields to add information about what is in the picture, when and where it was taken and by whom it was taken. This is the best way to insure that your pictures can be found again – all image archiving and storage systems work with metadata.

- SECOND EDIT – narrowing the selection of images down to those that will make it into the final edit or the selection that will be delivered to the client.

- CONVERT – taking the RAW images from the final edit, making adjustment to colour, exposure, brightness, contrast etc using a RAW converter and then saving the toned images to the required file format.

- RETOUCH – opening the images into Adobe Photoshop or a similar application to remove dust spots, make subtle (but ethical) changes that cannot be made in the RAW converter, which, these days, are very few.

- SAVE – the final stage before sending to the client is to save the edit in the format that the client requires either JPEG or TIFF are most likely.

- DELIVER – most images these days are delivered using the internet. FTP is the most efficient but you may also be asked to email pictures, create web galleries, upload to third party viewing sites or simply burn everything to a disc and put them in the post.

- ARCHIVE – make sure that you back up copies of everything that you may need again. External hard drives, cloud storage systems and op?cal discs are the most common options. Multiple back ups are the best way to avoid losing your images due to the ageing of materials or the failure of drives.

- RELAX – that’s the end of the process!

Folio photo #09: Bournemouth grave digger, October 2008

Dave Miller has been working for the cemetries service in Bournemouth since leaving school. These days he even lives in a house inside one of the local graveyards. Photographed at dusk in Bournemouth’s North Cemetry for The Guardian. They were running a whole series of pictures of people who do slightly unusual jobs and they times this particular feature to run at halloween.

This frame features four separate flash units – one of which is down inside the grave (which was otherwise empty). Dusk is my favourite time of year for shooting pictures and this particular sunset was very colourful. If you’d like to know even more about this picture, go to this technique page

The day after a bad day at the pool

When we first went digital back in 1998 there were a lot of lessons that we had to learn for ourselves. There hadn’t been much work done by others and there were a lot of mistakes that we made and learned from. One of the worst things to happen to me wasn’t until June of 2006 – long after we all arrogantly thought that we had learned what there was to learn.

I went to shoot some pictures at a swimming event and the atmosphere was loaded with what smelled like chlorine. My cameras had got steamed up quickly and took a while to de-mist and I thought nothing of it, shot the event on a pair of Canon EOS1D MkII cameras and edited my pictures as normal. Nothing wrong… so far. The next day I went to shoot portraits of a young student who had been shortlisted for a writing award – totally run-of-the-mill. The job went well, the pictures looked great on the back of the cameras but when I imported the files from the first camera into the computer I went as white as a sheet.

Dirt on the chip was a common problem, the odd bit of dust that showed up when you stopped the lens down but nothing had prepared me for the amount of spots that were on these pictures.

Thousands of small, circular bright spots in the same place on every single frame. I was swearing, sweating and worrying in equal measure as I put the memory card from the second camera into the card reader. If they were as bad, this job was going to take weeks to edit and retouch. Massive relief… the second camera hadn’t suffered from the same fate. The tighter pictures shot on the longer lens all had the spots whilst the wider pictures shot with a wider lens had none of them. The bonus was that some frames on the spot-free camera were also shot on a longer lens so I had a few spot-free tight portraits too. The panic was almost over but it was clear that at least two or three of the heavily spotted pictures should be in the edit so I spent most of that evening and night painstakingly getting rid of the spots. One-by-one.

After a thorough clean by FIXATION UK the camera was as good as new. The spots were crystallised chlorine and quite why they were only on one of my two cameras used on the bad day at the pool I will never know. People have theorised about having taken the lens off of one and not the other, damaged weather seals, some sort of coating on the chip of one camera that either attracted or repelled the crystals – who knows?

The morals of this story are these:

- Shooting with two cameras is always a good idea

- Using a professional to clean problem dirt off of the chip is a great idea

- Shooting with some wide and some long lens images on both cameras is a good idea too

- Be careful when taking lenses on and off in unclean environments

- Retouching spots is a right royal P.I.T.A

That camera went on to give great service for two more years and was sold on having been cleaned and serviced. These days I use a pair of 5D MkII bodies which don’t have the same environmental seals as the 1D series. If I were a rich man, I’d want to own the new 1DX when it comes out!

Resolution, and not just for the new year…

When a member of my family asked me earlier this week what my ‘new year resolution’ was, I was tempted to answer “300 dpi”. I would have laughed but I’m afraid that the rest of the family would have just given me that old-fashioned look that says “Neil is laughing at his stupid jokes again”. For the record I want to get fitter, lose some weight, shoot better pictures and love everyone.

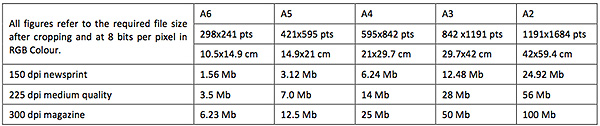

To photographers, designers and anyone else who handles photographs resolution is an important concept. Get a few photographers together and someone will complain about a client whose comprehension of the concept of resolution is so poor that they have rejected huge files just because they hadn’t been saved at 300 dpi. What is 300 dpi anyway? Does it have any relevance in todays’ digital world?

Put simply, DPI is an output term. It describes the number of dots per inch that the printing system will place onto the paper and, generally speaking, the more dots you have the better the quality. Of course if you have cheap paper that soaks up ink too many dots just produces a mulchy mess. Newspaper quality is a case in point: try to stick more than the right amount of ink down and the paper will get soggy and rip whilst going through the presses. Your inkjet printer at home might be capable of 2,880 dots per inch but that doesn’t mean that you have to save your pictures at that size. So much software these days has the ability to re-size and re-interpret images to make them work.

Don’t get me wrong, it is always best to send pictures to commercial printers or reproduction houses at the right size at the correct resolution and properly sharpened but some of the nonsense talked by people who don’t understand is very frustrating.

Photographs are actually measured in pixels per inch or pixels per centimetre but even that misses the point. What actually matters is the number of pixels that make up the image. You can have a picture that measures 3,000 pixels along one side and 2,000 pixels along the other (6 million pixels in all) and that is really the important fact. At 72 pixels per inch (the normal internet resolution) that would appear as a huge picture. If the same 3k x 2k pixel image was saved at 150 pixels per inch (about normal for newsprint) it would still be 50cm wide whereas at 300 ppi it would be 25cm wide. Actually switching between resolutions is easy and it makes no difference to the image quality (unless you repeatedly re-save in a lossy format such as Jpeg). All that really matters is the number of pixels.

Even going back to the days of scanning negatives on the venerable Kodak RFS machines into Photoshop version 2.5 where an original 35mm image measured 24mm x 36mm (that’s 864 sq mm) meant that every picture was still 24mm x 36mm but had a resolution measuring up 2500 ppi it was a few clicks of the mouse to change the picture to the required resolution at the required size with no damage done – with the possible exception that the low power of the computers meant that it took more than a few seconds.

Exactly who trained these people who don’t get this concept is beyond me. It is as simple as it is logical. My new year resolution is, therefore NOT 300dpi. I’m going for 254 ppi or 100 ppcm along with a bookmarked link to this blog piece so that I can refer people to it as, and when, required.

Original dg28.com technique pages

Between January 2000 and June 2008 I posted a large number of technique examples taken from my daily work to show how I used light in an era where digital cameras were pretty poor at ISOs over 800 or even 400 in the case of the venerable Kodak DCS520. These days flash is a creative choice rather than a technical necessity but the techniques still stand up.

One of the technique pages was entitled simply “Why we use lights” and it is an extreme example of just how much difference some judiciously used flash can make. Early Autumn on a Friday evening in the UK isn’t often a time when the best opportunities to shoot great pictures present themselves. This one, was a real exception.

The subject of the portrait runs an educational organisation that serves a coastal area near where I was born. I should know the area like the back of my hand but I don’t and when my subject suggested that we went up on top of the Isle of Portland (not an island at all, just a peninsula!) I thought that it would make a decent enough backdrop but that the view might be obscured by mist. The two pictures below were taken with different lenses but they were taken within a few seconds of each other and show just how much of a difference a bit of flash can make.

Back in 2008 when I “retired” these pages I wrote the following as a background to my philosophy regarding portable location lighting:

A lot of news photographers don’t think that they are allowed enough time to light pictures, so they rely on their hot shoe mounted flash or on moving their subject into the daylight. If your kit is lightweight and well planned, if it’s reliable and quick to assemble then you can light as much of your work as you want to. I tend to specialize in editorial portraiture, so that is the area of work that I’m going to talk about.

When I was writing these pages my basic kit was one Lumedyne 200 joule pack, one Signature head, two regular batteries, one stand, an umbrella, a Chimera softbox and a Pocket Wizard kit – all in one sling bag. Since May 2009 that all changed and the Lumedyne kit was replaced by an Elinchrom Ranger Quadra system. I still like the Lumedynes but the Elinchrom is a few percentage points better! In October 2003 I added an Umbrella Box to my kit in the hope of replacing two light modifiers with one, which has worked in some ways but I have to confess that I go through phases of using each of the light modifiers for a while and then switching.

In the years when I was a staff photographer and posting regular monthly galleries as well as technique and opinion pages my website was getting up to 20,000 unique visitors a month. Numbers have clearly dropped off now that new content hasn’t been added for three and a half years but I’m still amazed by the the fact that in one day last month the technique home page still got 996 unique visitors.

Some day, I am going to write a book – yeah, I know – we all say that… The backbone of that book will be an up-to-date explanation of the theory behind some the 60+ technique samples posted on the original dg28.com. In the meantime, be my guest – follow the link below to the old technique pages and have look around. Be warned: one very well known blogger claims to have lost an entire night’s sleep doing just that.

Folio photo #08: Peter Snow, London, May 2004

Peter Snow, BBC sephologist, journalist and newsreader photographed after an interview at a central London hotel for a “My Best Teacher” feature for the TES Magazine.

He had a book and a TV series with his historian son at the time and the interview was one of a long series that he had already done that day. The room was cramped and poorly lit and so I used a medium sized soft box very close to him to keep as much light off of the background as possible. One picture editor that I worked with used to call this very tight crop the “egg cup” because it was as if someone had flattened the top just like one.

Mindset – small word, big concept for news photographers

Written in 2002, this opinion piece still holds very true nearly ten years later…

What’s the difference between a photographer who takes pictures for fun, another who struggles as a professional and one who is on top of their game? The answer, well there are many but the top of my list is….mindset

It’s a pretty innocuous word, but it makes a massive difference. As I sit here writing this I’m trying to formulate some thoughts ahead of a talk to a group of postgraduate news photographers. Snappy titles are always a good start – according to the “Lecturing for Dummies” handbook so “Mindset” it is.

Next step – arresting opening sentence. That will have to wait until I have better formulated my ideas, but my handbook tells me that if you get people’s attention at the beginning you have won fifty percent of the battle and if you don’t you will waste a lot of time getting it back. Well, that’s a bit like writing and (spot the cheasy link) an awful lot like being a news photographer.

The narrative that runs through a well shot photo story or a well written essay is remarkably similar. I have been trying to find a way of telling eager “news photographers in the making” that the message is more important than the way it is delivered and I have decided that it’s worth keeping the writing analogy going. Nobody denies that poetry is literature and everyone has respect for well written short stories. Good authors are comfortable with their medium, they structure their work and use words economically. Good photographers mirror this. The common thread is mindset; shaping what you have into what you want it to be. I’m not saying that you pre-judge an issue, but rather that you should edit before you shoot, as you shoot and after you shoot to tailor your pictures to a particular format.

If you are working towards an exhibition you work one way – adopting the right mindset, and if you are shooting a single image story you work a completely different way. And then there are the differences between making and taking photographs, between being a welcome guest wherever you are or an unwanted intruder. News photography is a very broad church, with room for many ways of working and a lot of photographers find it very difficult to switch between the various sub-genres. It can be done. The temptation for photographers new to journalism to assume that only great long complicated narratives qualify as news photography is understandable. It is also one hundred and eighty degrees out. The thought that it takes real skill to tell a story in a single picture is a difficult concept to master but the greatest story-tellers know that less can often be a whole lot more.

It’s all in the mind. If you have a month to shoot a spread you can afford a few days (let’s say three to make the comparison easy) to acclimatise. If you have an hour to shoot a single image story and you take the same percentage of the job time to settle in, you’ve only got six minutes. You know what the score is, so you adopt the right approach before you start. News photography, when it’s stripped down, is a really simple idea. You take pictures and you make pictures that tell stories. You can use photographs to spell out what you want to say, you can use them to intrigue the viewer or you can use them to infer things.

Good journalism often uses words, but it uses photographs just as often. If the photographer is thinking straight and can concentrate on the end product, good photography becomes great news photography.

Final step – the clever conclusion. I would advise anyone coming into the profession to read some good poetry and a few good novels, to work out how they were structured and to try adapting the simplicity of poetry to their photography. Why? The answer is all too simple, photography is all about creativity and it’s all about mastering the technical aspects but most of all it’s about a state of mind – a mental process – mindset.