When you work with one camera and you shoot RAW all of the time it really doesn’t matter if that camera has a tendency towards magenta, yellow or cyan – the shift will be consistent and you can cope with it very easily in post-production. If, on the other hand, you work with more than one camera and each of them has a subtle shift in a different direction then your workflow can be slowed down when you have to constantly colour correct images shot under identical lighting in different directions. Like all things in photography, there is more than one way to solve this problem.

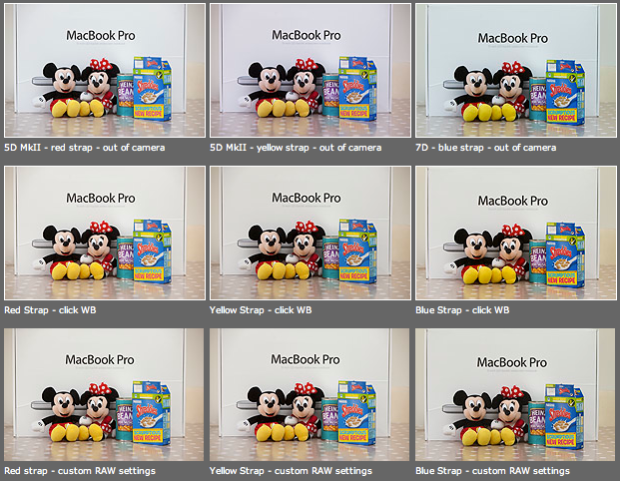

As you can see from the top row of images above – the three cameras that I use have different colour shifts with my slightly newer 5D MkII (codename yellow strap… because it has a yellow strap!) displaying quite a strong magenta shift whilst the 7D (codename blue strap, you can guess why) is a little cold and my oldest 5D MkII (red strap) is pretty neutral but maybe 1/3 of an f-stop brighter. I am going to use the red strap body as my basis for changing the colours on the other two a) because it is the most neutral to start with and b) because it has been serviced and cleaned by Canon quite recently.

Obviously these pictures were shot under controlled conditions using the same light source, the same lens on a tripod and have been converted from their RAW using no adjustments whatsoever. I shot multiple frames using each body as a sample just to make sure that there was no shift between frames on the same camera.

The second row of examples are the same RAW files with a white balance applied to exactly the same spot on the white box between Mickey and Minnie’s ears. As you can see this gets us a whole lot closer to matching the pictures for colour and this technique is fine when you have something in the frame which allows you to use the eye-dropper tool in Adobe Camera RAW (and in other similar raw conversion applications) and it is also fine when you only have a few images to process in this way. If you shoot an event where there are hundreds of frames, then you would spend an unnecessary amount of time balancing in this way.

The third row of examples utilises one of the cool features of the latest versions of Adobe Camera RAW in either Photoshop or Lightroom (and I’m sure that other software does this too) which allows you to set a default set of settings ranging from white balance to black levels, contrast, saturation to sharpening and noise control for each camera which the software detects from the serial number in the EXIF data as you bring it into the RAW conversion control pane. This is great for a lot of work and is a good option if you usually shoot on a fixed white balance.

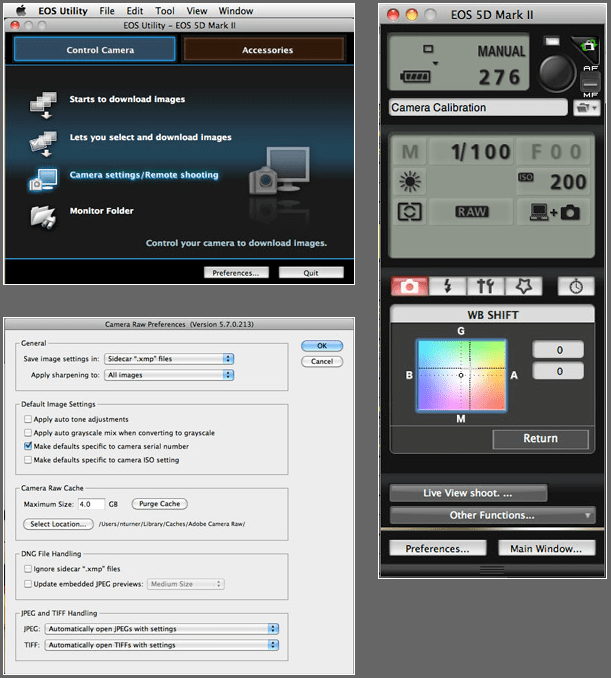

These three techniques work for pretty much every digital camera and every scan. Some, more modern and more expensive, cameras allow you to go one crucial step further and that is to tell the camera to automatically shift by a fixed amount of colour for every frame – so that if your camera has a magenta shift like my yellow strap camera you can counterbalance that in camera and your images will show up as they should – no matter which white balance you are using at the time. The next few illustrations are based on a Canon 5D MkII using Canon’s own EOS Utility:

The illustration above top left of the three shows the home screen of the EOS Utility application and the “camera settings/remote shooting option is what you need.

This brings up the window on the top right which has an option marked WB shift that allows you to control the cross hairs and set an exact shift for the camera that is connected at the time. It is simple and very, very useful.

The illustration bottom left refers to the technique in Adobe Camera RAW (Photoshop CS4 in this case) in which you set a custom import for each camera and this is the preference pane that you need to find it.

It would be great if there was some software that allowed you to perform an exact “chip” calibration in the same way that you can calibrate a computer screen. Of course, the ability to calibrate the LCD on the back of a DSLR would be cool too but in the mean time here are three ways that you can use the combination of a good RAW converter and your camera’s built-in options to get all of your cameras working the same way as each other. It takes time, it’s fiddly but will save you a great deal of hassle over the course of a few weeks work.